Bridging Cultural Divides – Stories from Chairman Mao’s Personal Russian-Chinese Interpreter

Zhe Shi – Chairman Mao’s personal Russian-Chinese interpreter

MAO’S PERSONAL INTERPRETER, ZHE SHI AND THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY

Born in 1905, Zhe Shi was a Chinese intelligence cadre trained in the Soviet Union’s military academies in Kiev and Moscow. He became the primary Russian interpreter for chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, Zedong Mao, during the last years of the Chinese Civil War. Shi interpreted high-level negotiations primarily on topics of increased Soviet military and economic aid for the Communists.

Shi interpreted for Mao during the final retreat of GMD leadership to the island of Taiwan and ultimately the successful outcome for the Communist Party.

BACKGROUND: A CHINESE GENERATIONAL TRAUMA

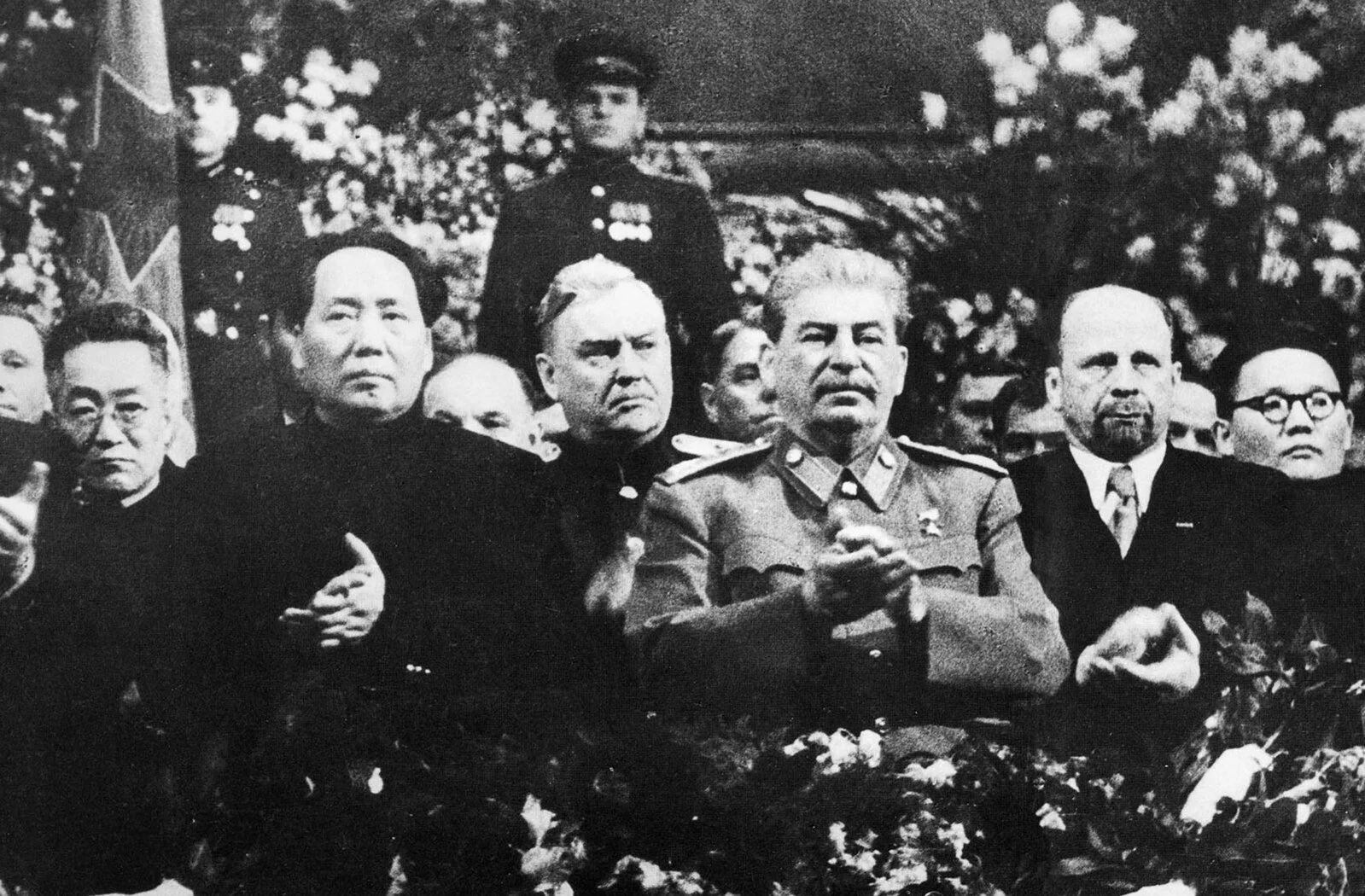

From the left: Mao’s interpreter Zhe Shi, Zedong Mao, Nikolai Bulganin, Joseph Stalin, Walter Ulbricht, and Yumjaagiin Tsedenbal

At the end of the 1940’s, China had suffered decades of civil war. With the Chinese Communist Party and the nationalist Guomindang (GMD) fighting for influence and territory, mainland China was also disrupted by the Japanese invasion from 1937-1945.

U.S. backed GMD was in the late 1940’s exhausted by both the Japanese invasion of China and military strategic errors in their fight against the Chinese Communist Party. The Communist Party simultaneously fought the Japanese front, too, and underwent years of struggle against a GMD they saw as a potential existential threat should the U.S. intensify their economic and military support for GMD.

Millions of Chinese died in this decade-long trauma for the entire nation.

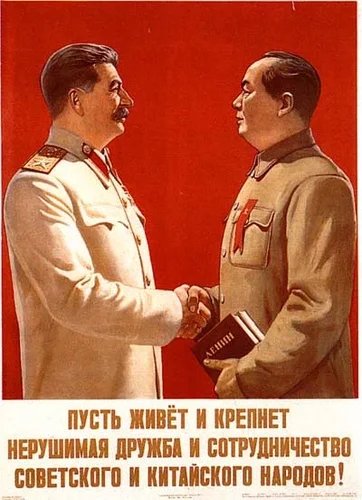

Stalin and Mao shakes on it

“Long Live the Strong Friendship and Cooperation between the Soviet and the Chinese People!”

❧

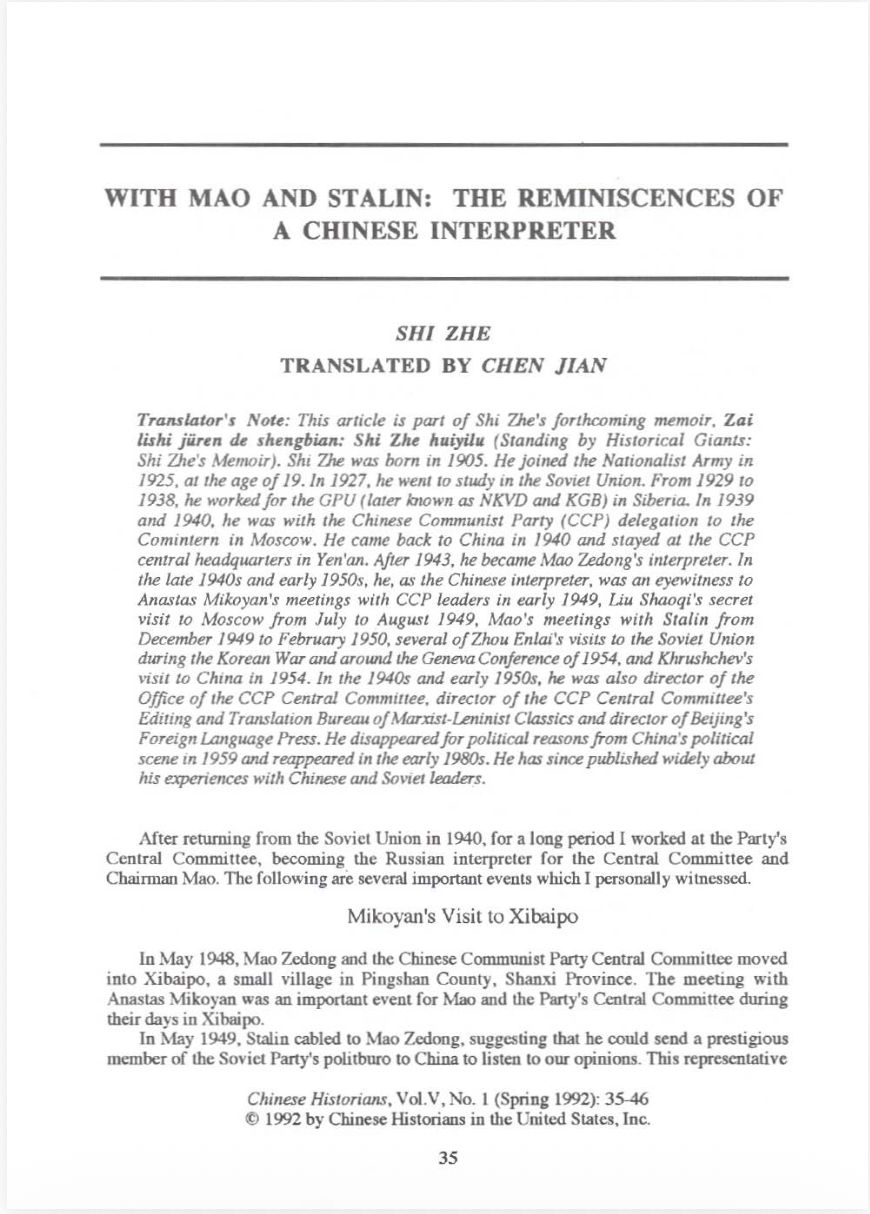

ZHE SHI’S MEMOIRS

– With Mao and Stalin: The Reminiscences of Mao’s Interpreter

In the 1970’s, Zhe Shi wrote his memoirs about journeys to the Soviet Union as a high-level aide to Mao during the critical last years of the Chinese Civil War in the late 1940’s.

Journeys, that were according to Shi facilitated by early-tech aeroplanes with unpressurised, unheated cabins that would reach freezing temperatures at 10 kilometers altitude above the Russian taiga – rendering entire officials cadres of the Chinese Communist Party frost-bitten and even physically ill for days after arrival in the Soviet Union.

Arrive they did, however, on multiple occasions, and Shi’s experiences as an interpreter between Mao and Stalin in top secret, high-level meetings were astonishing as feats in themselves, as they were consequential for the following course of events on the European and Asian continent.

The deals forged in those meetings prompted a pivotal moment in the Chinese Civil War and shaped the Chinese Communist Party for years to come.

KEY PEOPLE DURING THE 1949 COMINTERN MEETINGS IN MOSCOW

Joseph Stalin – General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

Zedong Mao – Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party

Anastas Mikoyan – Deputy Chairman of the Soviet Union

Shaoqi Liu – Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission

Zhe Shi – Zedong Mao’s interpreter and Shaoqi Liu’s aide

FORWARDNESS VERSUS POLITENESS – THE PITFALLS OF TRANSLATING CULTURAL GAPS

DEFYING STALIN’S "RECOMMENDATIONS"

Following Sino-Soviet Comintern meetings in Moscow in 1949, Shi describes a situation four years earlier in 1945 during the Moscow meetings where the discussion point is Zedong Mao’s earlier decision to visit the city of Chongqing as part of a propaganda push. Stalin had expressed that Mao should not focus on a new propaganda campaign, but instead negotiate a peace with GMD.

Stalin also expressed security concerns specifically with Mao’s trip Chongqing since enemy units were present there. Stalin had explained that the risk of assassination was too high, and Mao’s and the CCP’s security ultimately meant the security of the Soviet Communists, too.

Mao’s delegation ignored this recommendation and went on with the propaganda campaign and their trip to Chongqing nonetheless, but without commenting answering Stalin’s telegram.

This Chinese act of defiance tells us two things: (1) Stalin felt in a position of power to dictate the course of trivial matters such as Mao’s day-to-day planning and (2) the Chinese did not directly answer to Stalins order, but simply carried out their plans anyway with no further comment – leaving room for interpretation in Kremlin.

Stalin brought this up in the 1949 Comintern meetings, and Shi’s memoirs dissects the power dynamics across the dining table.

Stalin to the Chinese delegation on the topic of the Chinese Communist Party ignoring his 1945-telegram:

“You Chinese comrades are too polite to express you complaints. We know that we have made ourselves a hindrance to you, and that you did have some complaints, but you would not tell them to us. You should certainly try to judge if our statements are correct or wrong, because we may give you erroneous advice as the result of lacking understanding of the true situation in your country. Whenever we have made a mistake, you should let us know, so that we may notice the mistake and correct it.”

Zhe Shi reflects on this divergence of approach toward communication by respectively the Russians and the Chinese.

Shi:

“This was the first time that Stalin engaged in such frank self-criticism before the CCP delegation, and it went totally beyond our expectations. Our delegation had never requested him to engage in such self-criticism; nor had we tried to criticize him. As a matter of fact, we even had never thought of doing this.”

Amusingly, Stalin confronts the Chinese delegation with their defiance in 1945 just moments after Stalin “inviting“ the entire delegation to watch no less than four (4!) entire films of his selection in a row. One of the films was a detailed documentary about the technical process of conducting a nuclear bomb test of a certain type of Soviet atom bomb. According to Shi, this nuclear documentary evoked grand impressions with the Chinese delegation.

Stalin was quite the moviegoer – he had a habit of “inviting” the cadres to watch films. Stalin, of course, would always pick which one.

CHUMMY STALIN AND STERN MR. LIU

– STALIN’S SPEECH AND LIU’S RESPONSE HERETO

AT A MOSCOW NIGHT MENU BANQUET IN LUSH SURROUNDINGS

With excellent food and ample liquid supplies, Stalin at one point raised himself and put forth a toast directed at one of the members of the Chinese delegation – vice chairman of the Chinese Central Military Commission, Shaoqi Liu.

Shi interpreted.

It was a friendly toast of good spirits, even on the chummy side. The toast, which evolved into a speech, touched upon subjects such as the continued cooperation and the Soviet and the Chinese progress toward communism, in respectively both their own, unique ways.

Stalin’s toast was a praise of the Chinese Communist Party – and there was the indication that the Soviets could learn much from the Chinese.

Then there was also the rather chummy notion of the Soviet Union being the “elder brother“ and the Chinese Communist Party the “younger brother“ in this implied brotherhood of nations.

Stalin’s banquet speech to Shaoqi Liu, in front of the rest of the Chinese delegation:

“It is possible that we Soviets might know more than you do in the general theory of Marxism. But in terms of how to apply the general principles of Marxism to practice, you have much experience that we should learn from. In the past, we have learned a lot from you.

One nation has to learn from another nation. Even a small nation will have many strong points that can be learned by the others. I have he. ard many stories about the extraordinary diligence of the Chinese people. This is what we should learn from you.

You are calling us the 'elder brother' today. I sincerely hope that the younger brother will one day catch up with and surpass the elder brother. This is not only the hope of my colleagues and me; this is the historical rule: the latecomers will eventually surpass the advanced ones. Let's toast to the younger brother surpassing the elder; let's toast to the younger brother's rapid progress.”

Following the inevitable applause by the Chinese delegation, Shaoqi Liu now raised, and a silence befell upon the room.

Liu:

“The elder brother is always the elder, and the younger is forever the younger. The Chinese should learn from the elder brother all the time.”

Liu continued with a rather dry answer. According to Shi, who was interpreting, Liu did not retribute Stalin’s warm vibes, and ended his response rather quickly.

From across the table, Shi quitely and worriedly noted that this was a case of Liu refusing to accept Stalin's toast. Shi also descibed how the entire table felt uneasy following Liu’s comments, especially the Chinese delegation. Shi being a professional interpreter, maintained his impartiality.

Shi wrote about the incident:

“Feeling embarrassed, the Soviet comrades all came to advise Liu to accept Stalin's toast, which was full of good wishes and friendly feeling. They simply could not understand why we Chinese would not accept such warm wishes as expressed by Stalin.”

Stalin then got up again:

"Isn't it correct that the younger brother should surpass the elder? I mean that the younger brother should make extra effort to pursue rapid progress, so that he will possibly surpass the elder brother. This also means that you need to accept more international responsibilities in the future.

Now, China is not fighting for her cause while isolated in the world. This will allow you to achieve more rapid progress and development, and naturally, you will need to bear more international responsibilities."

Still, Liu Shaoqi would not “yield a single inch”, according to Shi. The rest of that night, Liu held a certain grudge against Stalin!

Stalin’s notion of a certain hierarchy in this complicated power dynamics soon turned out to be an important focal point of the entire Comintern meetings, and it was also something interpreter Shi would reflect on later in his career. Because it revealed a significant divide between the two cultures.

One could say this situation was an example of a certain straightforwardness in the Russian culture, offset with the honor culture of the Chinese.

Shi reflects on this cultural gap that exists in parallel to the complex power dynamics of the Stalin-Mao relationship:

“The Soviets were apparently astonished, for by Russian custom, it was normal practice to say something beautiful while proposing a toast, and it was extremely impolite to refuse to echo it. But Liu Shaoqi must have taken all of this too seriously, and he must have felt that it would be too arrogant for him to accept Stalin's statement.

The differences between two cultures and two sets of customs, together with the long-time psychological chasm between the Soviets and us, caused this strange episode.

Of course, I will never forget it."

❧

THE PITFALLS OF TRANSLATING FROM RUSSIAN

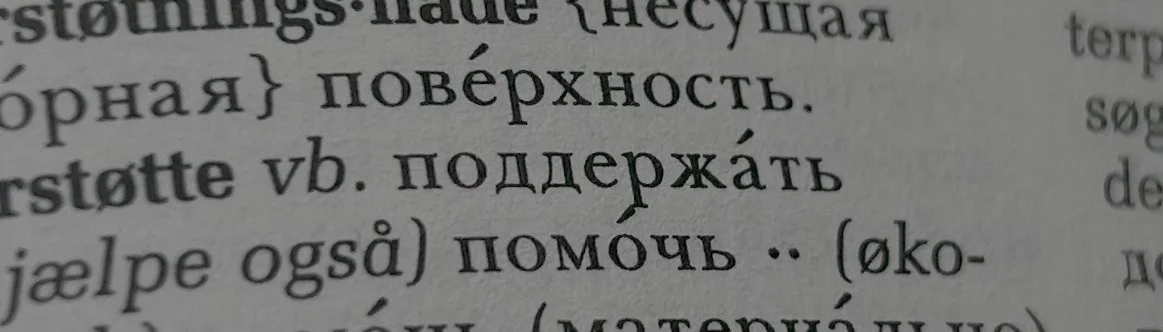

ASPECT

Most Russian verbs come in two versions – or two “aspects”. The imperfective aspect and the perfective aspect.

The imperfective aspect is used is an action is ongoing, habitual or repeated.

The perfective aspect is used when an action is completed, or if the context is single event or future-oriented.

An example of this nuance is a 2022 debate between Vladimir Putin and and the director of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service, Sergei Naryshkin. Putin asked Naryshkin to express his stance on whether Russia should recognize the separatist regions Luhansk and Donetsk as independent states.

Naryshkin used the perfective aspect of the word for “support” in his answer: “Я поддержу.”/”I will support, limitedly, or at one point.”

Putin immediately demanded a clarification: “Поддержите что?”/”What will you support?”

Naryshkin nervously corrected himself, and shifted to the imperfective aspect of the same verb: “Я поддерживаю.”/”I fully support.

2. ACTIVE AND PASSIVE VOICE

Many languages employ both the active voice and the passive voice (e.g. “John wrote the book” vs. “the book was written by John”) – depending on whether or not there is a known “agent” in the syntactical understanding.

However, in the Russian language, the passive voice is used in a for outsiders perhaps peculiar way – the reflexive “ся“-passive. This is particularly interesting in a translational context, because of its intense focus on the internal processes of a given event – and not so much on the causality of it.

“The house is being build” is a common passive in the English language. In Russian, it commonly translates to “дом строится“/”dom ctroitsya”, which literally means “the house is building itself“, i.e. in an inward, reflexive way.

There is a focus on the “process” rather than the “agent” (or“doer”).

3. GENDER

Russian nouns come in three genders – masculine, feminine and neutral. Chinese nouns do not have genders. In Russian, the verb also takes shape depending on the gender of the noun – effectively revealing information about the agent (or the “doer of deeds”) in a given context.

An example: In order to express in Russian the following sentence – “I went for a walk” – the translator must know who “I“ am. Otherwise the translator would have to resort to guessing, applying gender at random.

Guessing could theoretically result in false information being produced.

❧

From the left: Zhe Shi, an unknown woman, Zedong Mao and Anastas Mikoyan

There are countless cultural anecdotes and linguistic subtleties to be found in Shi’s memoirs, With Mao and Stalin: The Reminiscences of Mao’s Interpreter. (Access institutionally restricted, see below).

❧

SOURCES

Shi Zhe & Chen Jian (Translator) (1993) With Mao and Stalin: The Reminiscences of Mao’s Interpreter Part II: Liu Shaoqi in Moscow, Chinese Historians, 6:1, 67-90

Encyclopedia Britannica