Ultimate truths are beyond human grasp, yet we continue to reach for them – Arthur Schopenhauer’s answer to the final metaphysical question

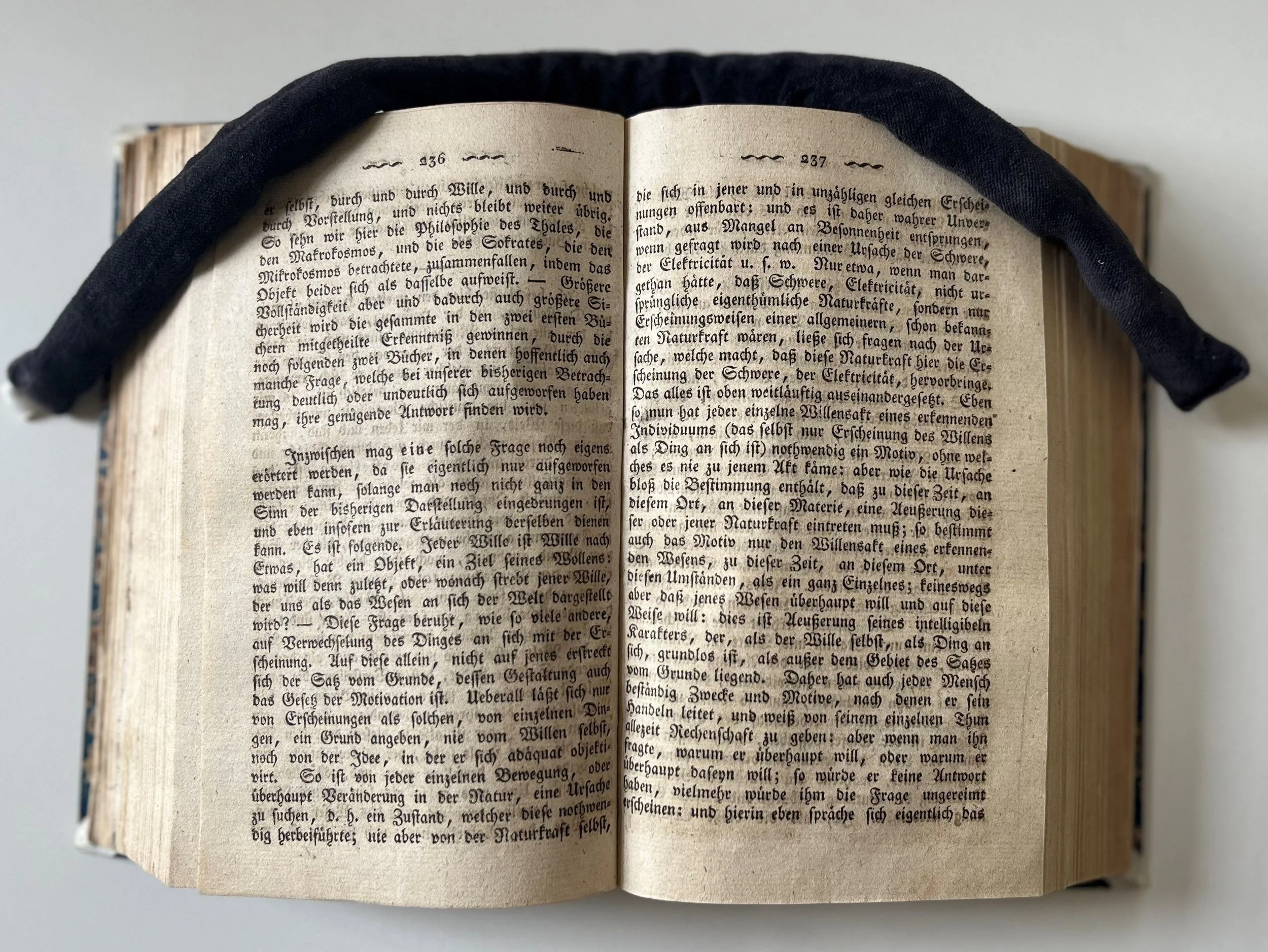

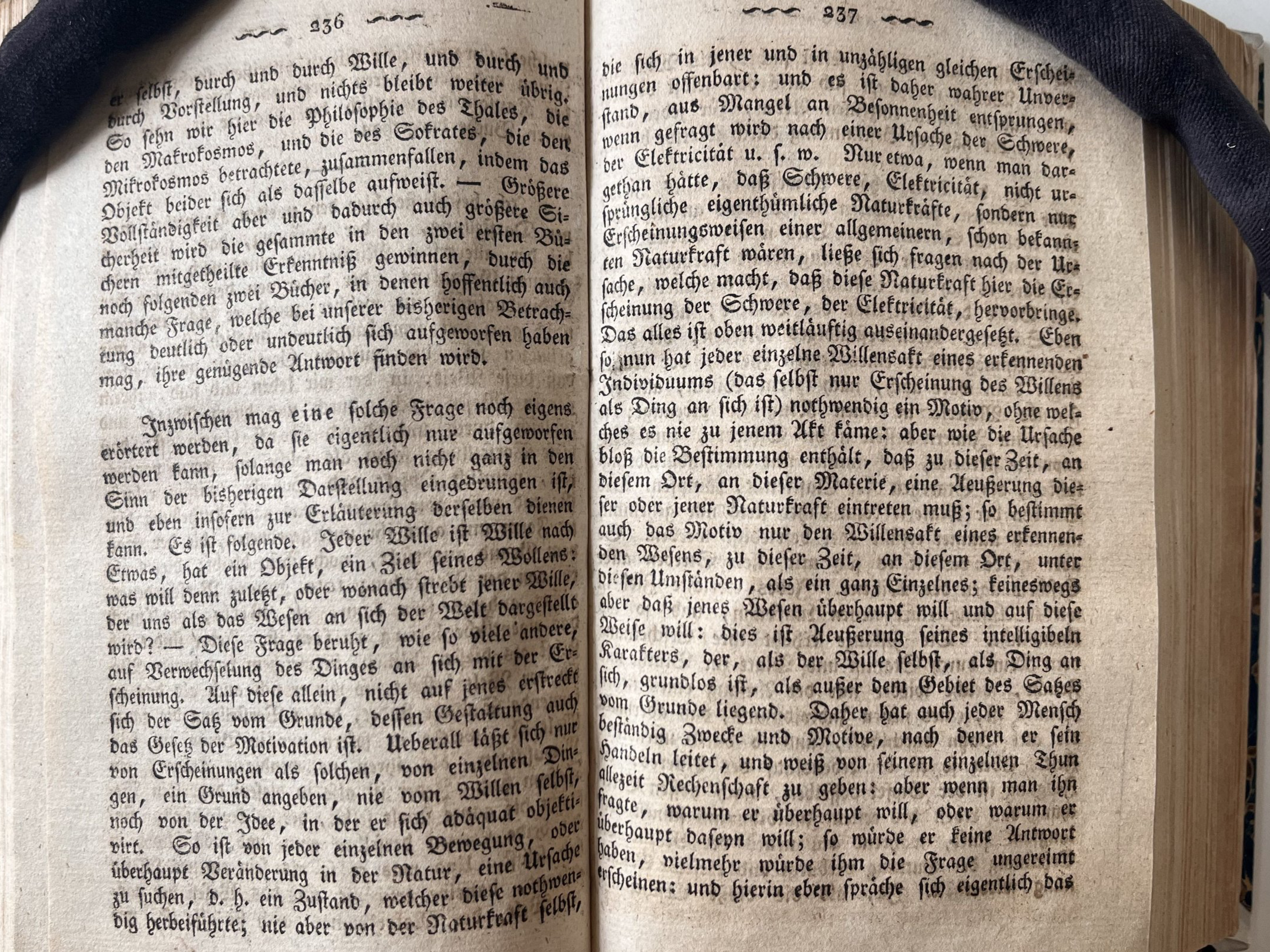

A central concept in Arthur Schopenhauer’s Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung, 1819, (The World as Will and Representation) is the Wille zum Leben (the will to live).

Wille zum Leben can be described as a fundamental force in nature which makes everything act as if it strives to persist and maintain itself.

(Schopenhauer-original in the picture was kindly lent to me by the German State Library in Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin).

❧

I have selected this short passage from the book, because it captures Schopenhauer’s metaphysics in a relatively clear and direct way, and because it presents his thinking about two key metaphysical concepts, namely the “Ersheinigung“ and the “Ding an Sich”, in an interesting way.

In my short article here, I will provide a short explanatory framework to aid further studies into answering the questions:

1. what is the nature of phenomena?

1a. can true statements be said about phenomena?

Schopenhauer starts on page 236 of “Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung” with the following question, as response to previous inquiry:

In a nutshell: Does every will point toward something, does it have an object and does it have a goal of its willing? What ultimately does that will want, and what does that will strive for, which is presented to the world as the essence in itself?

He then notifies us that “this question, like so many others, rests on confusing the thing-in-itself with appearance”. But before we dive into this now emerging terminological confusion, and before we attempt to look for answers, let us first look at the raw material at hand.

Here, I first transcribe to modern German from the knotty altdeutsch (the book is written in Frakturschrift), then translate it to English.

❧

Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung, 1819, P. 236-237

TRANSCRIBED TO MODERN GERMAN TYPE

(page 236)

Inzwischen mag eine solche Frage noch eigens erörtert werden, da sie eigentlich nie ausgeworfen werden kann, solange man noch nicht ganz in den Sinn der bisherigen Darstellung eingedrungen ist, und eben insofern zur Erläuterung derselben dienen kann.

Es ist folgende. Jeder Wille ist Wille nach Etwas, hat ein Objekt, ein Ziel seines Wollens: was will denn zuletzt, oder wonach strebt jener Wille, der und als das Wesen an sich der Welt dargestelt wird?

– Diese Frage beruht, wie so viele andere auf Verwechslung des Dinges an sich² mit der Erscheinung¹.

Auf diese allein, nicht auf jenes erstreckt sich der Satz vom Grunde, dessen Gestaltung auch das Gesetz der Motivation ist. Ueberall lässt sich nur von Erscheinungen als solchen, von einzelnen Dingen, ein Grund angeben, nie vom Willen selbst, noch von der Idee, in der er sich adäquat objektiviert.

So ist von jeder einzelnen Bewegung, oder überhaupt Veränderung in der Natur, eine Ursache zu suchen, z. B. ein Zustand welcher diese nothwendig herbeifürhrte; nie aber von der Naturkraft selbst, …

(page 237)

… die sich in jener und und in unzähligen gleichen Erscheinungen offenbart: und es ist daher wahrer Unverstand, aus Mangel an Besonnenheit entsprungen, wenn gefragt wird nach einer Ursache der Schwere, der Elektricität u.s.w.

Nur etwa, wenn man dargethan hätte, daß Schwere, Elektricität, nicht ursprüngliche eigenthümliche Naturkräfte, sondern nur Erscheiningsweisen einer allgemeinen wären, ließe sich fragen nach der Ursache, welche macht, daß diese Naturkraft hier die Erscheinung der Schwere, Elektricität, hervorbringe.

Das alles ist oben weitläufig auseineandergesetzt. Eben so nun hat jeder einzelne Willensakt eines erkennenden Individuums (das selbst nur Erscheinung des Willens als Ding an sich ist) notwendig ein Motiv, ohne welches es nie zu jenem Akt käme: aber wie die Ursache bloss die Bestimmung enthält, daß zu dieser Zeit, and diesem Ort, an dieser Materie, eine Aeußerung dieser oder jener Naturkraft eintreten muss; so bestimmt auch das Motiv nur den Willensakt eines erkennenden Wesens, zu dieser Zeit, an diesen Ort, unter diesen Umständen, als ein ganz Einzelnes; keineswegs aber daß jenes Wesen überhaupt will und auf diese Weise will:

dies ist Aeußerung seines intelligibeln Karakters, der, als der Wille selbst, als Ding an Sich, grundlos ist, als außer dem Gebiet des Satzes vom Grunde liegend. Daher hat auch jeder Mensch beständig Zwecke und Motive, nach denen er sein handeln leitet, und weiss von seinem einzelnen Thun allezeit Rechenschaft zu geben: aber wenn man ihn fragte, warum er überhabt will, oder warum er überhaupt dasein will; so würde er seine Antwort haben, vielmehr würde ihm die Frage ungereimt erscheinen.

❧

ENGLISH TRANSLATION P. 236-237

(page 236)

Meanwhile, this question may be discussed separately, since it can never really be raised until one has fully penetrated the meaning of the previous presentation, and can only serve to explain it in this respect.

In a nutshell: Does every will point toward something, does it have an object, a goal of its willing? What ultimately does that will want, or what does that will strive for, which is presented to the world as the essence in itself?

— This question, like so many others, rests on confusing the thing-in-itself² with appearance¹.

The principle of sufficient reason, whose form is also the law of motivation, extends to the latter alone, not to the former. Everywhere, a reason can only be given for phenomena (in themselves), for individual things, but never for the will itself, nor for the idea in which it is sufficiently objectified.

Therefore, for every individual change, or for every phenomena in nature, a cause must be established, for example the condition which resulted in the event; but a cause cannot be found for the natural force itself.

(page 237)

This feature is revealed in nature and in countless similar phenomena: and it is therefore a symbol of true ignorance, arising from a lack of calmness (for example when one asks for a cause of gravity, electricity, etc.)

Only if one had demonstrated that gravity and electricity are not original, peculiar natural forces, but merely manifestations of a “general” one – could one then ask for the cause that makes this natural force produce the phenomenon of gravity and electricity?

All of this has been extensively explained above. And every single act of will, stemming from a conscious individual (which is itself only an appearance of the will as a thing-in-itself), must necessarily have a motive, without which the entire “act” or “event” would never occur.

But just as the cause for anything merely contains the determination that at this time, in this place, in this matter, a statement of this or that natural force must occur; so too, the motive of this entire ordeal merely determines the act of will of a conscious being, at this time, in this place, under these circumstances, as a completely individual thing. But the ordeal does neither contain the assumption that that a being “has” a will, nor does it contain the assumption that a being has a “drive”, in its most simple understanding.

This is the expression of an clearly defined character, which, like the will itself, and like a thing-in-itself, is groundless, as lying outside the realm of the principle of sufficient reason. Therefore, every human being constantly has its purposes and motives, in parallel to which he guides his actions. The human knows how to give an account of his individual actions – at all times.

However, if one asked him “why” he wants to survive, or “why” he wants to exist at all, he would perhaps have an answer, but the question in itself would seem absurd and meaningless to him.*

❧

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Schopenhauer introduces a concept of will (Willensakt), and presents it as a hidden force pushing nature, and making it strive. It is unclear what specifically that goal is – but understand it is there.

Next up, he introduces two key concepts, namely “appearance” and “thing-in-itself”. Put short, he divides the world into two – one consisting of space, time and matter (a.) and then a “purer“ one, where normal understandings of the world no longer apply (b.).

(a.) “appearance” (Erscheinung)¹

(b.) “the-thing-in-itself” (das Ding an Sich)²

In the “appearing“ world, a reason can be given for phenomena (page 236).

A thing-in-itself cannot be readily understood or explained, and the governing factors are here unknown. We just know there is will. He says “nowhere can reason be given for the will itself, nor for the idea in which it is sufficiently objectified” (page 236)

Schopenhauers understanding of will is not a rational, self-conscious one, but instead one of “mindless, aimless, non-rational impulse”. The originally Kantian “thing-in-itself” is a study in itself – par excellence – both within philosophy and art alike. “Das Dinggedicht” (Thing-Poetry) is an entire genre within German literature, notably employed by Rainer Maria Rilke.

In short, Schopenhauer builds on Emmanuel Kant’s distinction between Erscheinung (appearance) and then the highly mysterious thing-in-itself.

“Erscheinigung” is understood as the world as we perceive it, structured by space, time, and causality.

“Thing-in-itself” is on the other hand what exists independently of our human perception. Schopenhauer identifies thing-in-itself as the “will”—the mindless, aimless force that underlies all phenomena and drives both nature and human behavior. (Stanford, Chapter 4. The World as Will)

I began this article by presenting an initial question raised by Schopenhauer in the book:

In a nutshell: Every will is a will toward something, has an object, a goal of its willing: what ultimately does that will want, or what does that will strive for, which is presented to the world as the essence in itself?

Cryptical as he is, Schopenhauer does not give us any easy answers to the question, but he does provide these explanatory building blocks, with which we can begin to construct a model of what the overarching message aims to convey. We learn that:

“a cause cannot be found for the natural force itself [the will]” (page 236)

“for every individual change, or for every phenomena in nature, a cause must be established, for example the condition which resulted in the event; but a cause cannot be found for the natural force itself. This feature is revealed in nature and in countless similar phenomena: and it is therefore a symbol of true ignorance, arising from a lack of calmness” (page 237)

“the ordeal does neither contain the assumption that that a being “has” a will, nor does it contain the assumption that a being has a “drive”, in its most simple understanding” (page 237)

Understand, that while there are explainable phenomena (for every phenomena in nature, a cause must be established, for example the condition which resulted in the event), the underlying force, meaning and raison d’etre cannot be established. A cause cannot be found for the natural force itself, and no situation feasibly contains the assumption that a being “has” a will.

❧

CONCLUDING REMARKS

1. Will as an underlying force of nature cannot be explained empirically, by scientific method, or by logical deduction. The argument falls apart too quickly. But we can, very carefully, pretend that there is such force, and that is manifests itself as a mysterious “something” out there – which inhibits a place beyond our realm, beyond human grasp.

1a. Based on this assumption, there exists concrete truths in the appearing world (the world of Erscheinigung). However, if we consider concrete truths beyond the phenomenological world as being placed deductively before, or at the time of, the manifestation of the will, they are then currently unavailable to us.

❧

* This translation is not scholarly vetted. Therefore, it may only serve as a coarse guide for the reader in this one instance alone, and may not be used for further studies of the topic or in other applications.

¹ “appearance” (Erscheinung)¹. Learn more here

² “the-thing-in-itself” (das Ding an Sich). Learn more here

SOURCES

Schopenhauer, Arthur. Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung Leipzig: Brockhaus , 1819. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Unter den Linden - Rara-Sammlung (R)

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/schopenhauer/? (Chapter 4. The World as Will)

Thanks to Cornelia and Daniela for helping me decipher Frakturschrift

IMAGES

Shadows on a wall, licensed via Unsplash